Geology’s Asmaa Boujibar gets new $300,000 NASA grant to research the building blocks of planet Mercury

How unique is Earth? How different is Earth from the other planets in the Solar System? And how different are the planets orbiting our sun than planets orbiting suns thousands or millions of light years away?

Heady concepts that most of us wouldn’t even begin to know how to answer – but those are the questions that Western Washington University Assistant Professor of Geology Asmaa Boujibar is trying to uncover in her lab, and a new 2-year, $300,000 grant from NASA will help push her closer to some of the answers she is seeking.

Unlike Mars, which has rovers on its surface directly collecting and sending data back to Earth, Boujibar’s current focus – the more mysterious planet Mercury – is much more reticent in giving up its secrets.

“We know a lot more about Mars than any other planet beyond Earth, thanks to data from rovers and Martian meteorites that fall on Earth. But for Mercury, we must work with laboratory simulations and remote sensing. All the work we do in my lab can only be based on remote sensing data, and a huge majority of that comes from the spacecraft Messenger,” said Boujibar.

Messenger was a NASA probe that orbited Mercury for 4 years, from 2011 to 2015, sending back uncounted bytes of new information, maps, and all the data it could gather from its instrument package before it finally lost orbit and impacted on Mercury’s surface.

“But what we got before then was gold,” said Boujibar. Now she and her team of grad students and undergrad researchers are mining that data for everything they can glean about Mercury’s geologic past, present and future.

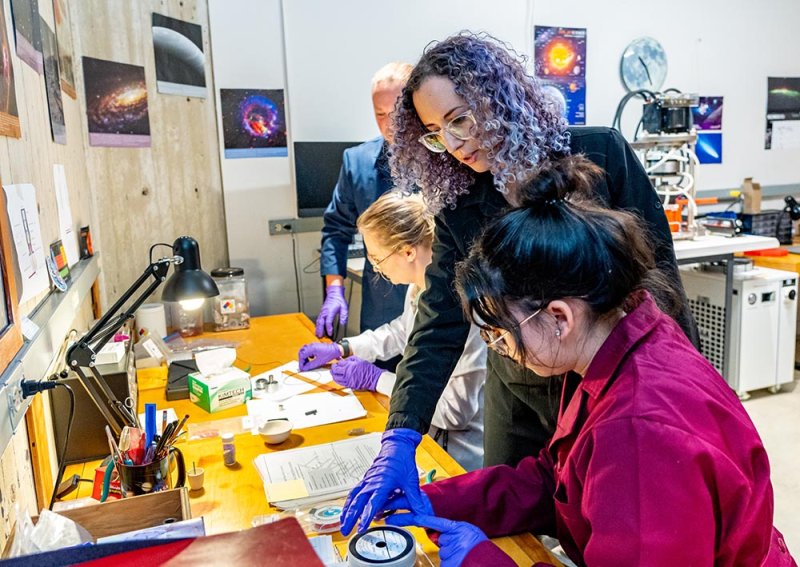

Boujibar is able to produce in her lab the same chemistry, pressures and temperatures that are present on Mercury – creating a little slice of that planet right here in Bellingham. Conducting experiments in that exotic environment to better understand what is happening on the surface and in the mantle and crust of what astronomers call “The Swift Planet” because of its rapid orbits of the sun gives Boujibar new insight into how planets like Mercury are born.

“We’re using laboratory data and what we know of Mercury’s geochemistry from the Messenger spacecraft to see what they can tell us about the formation of the planet,” she said.

One thing is for certain – Mercury is very different from Earth and Mars. Being the closest planet to the sun, of course, means we won’t be visiting anytime soon, as its daytime temperatures in the sunlight typically hover near 800 degrees Fahrenheit. All of its rocks are just as different, too – Mercury’s rocks have far less oxygen and far more sulfur than Earth’s or even those of Mars, meaning there are no analog rocks on Earth that can be used as proxies for Mercury.

Thankfully, Boujibar and her students are able to use her brand new lab to do a lot of the heavy lifting on some of these complex geochemical problems.

“The high-pressure, high-temperature laboratory enables us to simulate the interior of planets, including Earth. So, we basically combine data from the surface with experiments to figure out what the interior might look like, and construct a full picture of what the planet is made of, all the way to the core,” she said.

Additionally, her NASA grant will help students tackle the complex patterns seen on the surface of Mercury, by applying Artificial Intelligence. Data from MESSENGER showed interesting correlations between many aspects of the physics and chemistry of the planet, such as the topography, chemical composition, age, magnetic and gravity field. Now, we can lean on machine learning to process this large body of data and identify patterns unseen with traditional mathematical techniques.

“This project is very timely, since another spacecraft, launched as a joint venture between the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency called BepiColombo, will begin orbiting Mercury in December 2025. Our results will provide new hypotheses to test with data collected by this mission," said Boujibar.

Big grant, huge student opportunities

Boujibar’s NASA grant will fund a number of paid summer research opportunities for both graduate and undergraduate students in her lab, in addition to those already hard at work there, unlocking Mercury’s riddles.

Geology graduate student Richard Gwyn is using the data from Boujibar’s lab to complete his thesis – and more.

“My next few steps at Western are to finish this thesis up, then begin writing a formal publication for the Journal of Geophysical Research based on my modeling and experimental research here,” he said. “I plan on continuing my education to the final step by getting my Ph.D. starting in 2025, with a few universities still on the table.”

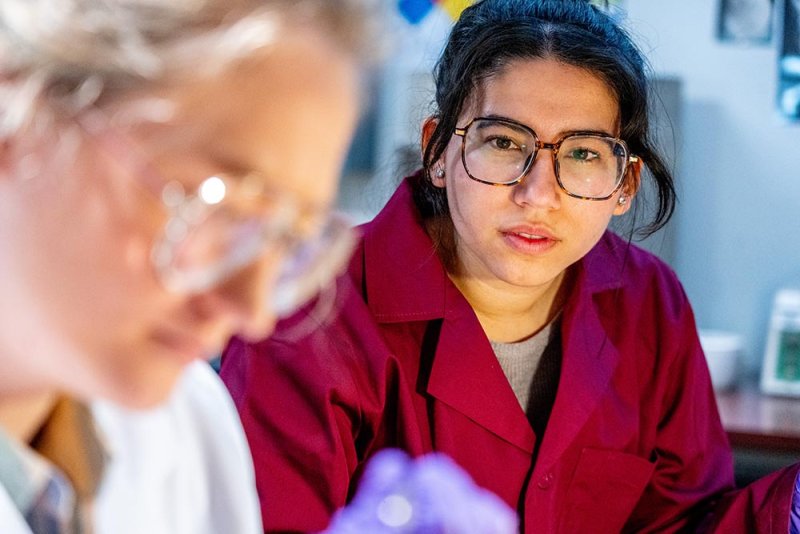

Fellow grad student Taylor McCombs said Boujibar’s lab has been the perfect place for her to discover where her true interests in research lie.

“I was drawn to Asmaa’s lab because I was able to implement my chemistry background with my love of geology and planetary science through experimental petrology. Being part of this group has enabled me to better determine which areas of geochemistry and planetary science interest me and to also develop my laboratory skills, which I plan to carry forward as I pursue further education,” she said.

Undergraduate Avery Valvano, a senior Geology major who is also minoring in business administration and astronomy, said the wide range of experiences in Boujibar’s lab – from tools to software to programming languages to data collection – will be a huge help looking ahead to graduate school in planetary science.

“Familiarizing myself with scientific tools, principles, and skills helps my resume become a little sharper -- and thus makes me more attractive as a candidate for both graduate schools and jobs," Valvano said. “Not to mention it is fun to do!”

From Casablanca to Bellingham

Boujibar is the first to admit that as a child, her goal wasn’t to get a post-doc appointment to NASA, or become a professor teaching students about the building blocks of planets.

“I didn’t know enough about it have a goal like that,” she said. “As a young girl growing up in Morocco, it just never dawned on me that I would be able to do any of this. It was just a case of someone following their interests.”

Boujibar grew up in Casablanca, the largest city in Morocco, and went away to college in France, getting her undergraduate degree and eventually a doctorate from the University Clermont Auvergne in 2014.

“I started my education in physics and chemistry, and then my fascination shifted towards geology and particularly volcanology. This passion propelled me into pursuing a master's degree focused on studying volcanoes, and an internship in Japan, where I explored the inner workings of the Earth. This experience solidified my dedication to the field, paving the way for my pursuit of a doctorate in rocky planet formation" said Boujibar.

After obtaining her doctorate, she secured a two-year postdoctoral appointment to NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

“Drafting my first postdoc proposal simultaneously with my thesis was challenging,” she said. “But despite knowing how difficult it was to get in, I pushed through, and it was totally worth it.

“Working at NASA JSC in Houston was incredible. I was able to access the labs where Apollo lunar samples are stored, as well as all the meteorites collected in Antarctica. Being able to see developments in space robotics and interacting with astronauts was an exceptional experience,” she said.

Her work at NASA unexpectedly made her a bit of a celebrity back home in Morocco.

“It turns out that my work has impacted young girls and women from Morocco, which is very gratifying. Some of them see in me the chance to pursue their own dreams in that way, which is wonderful,” she said.

After a second postdoc opportunity, this time at the Carnegie Institute for Science in Washington, D.C., Boujibar arrived at Western to begin her first teaching job in Fall 2022.

“It’s been great – I love the mix of student-focused teaching and research that is just such a huge part of the Western experience. The attention to students brings out so much of the humanity in me, making me feel deeply connected and engaged in their growth,” she said.

As for Mercury, Boujibar said she and her students will keep prying apart its data for secrets, one by one.

“Every riddle we solve seems to open up 10 more,” she said. “Which is just one of the wonderful things about science.”

Find out more about Western's Geology Department at https://geology.wwu.edu/.