WWU grad student part of research team seeking to understand Japan's earthquakes

Western geology graduate student Beth Novak spent all of December aboard a deep-sea drilling vessel off the Kii Peninsula in Southeast Japan with a 26-member research crew, drilling as deep as 380 meters into the Philippine Sea floor and collecting sediment samples.

Novak was one of the four paleomagnetists (scientists studying the record of the Earth’s magnetic field in rocks and history of motion of tectonic plates) on board, which had her working in the paleomagnetic lab, overseeing samples and writing and editing reports. Novak’s participation in the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program expedition was funded by a $3,000 grant from the Consortium for Oceanic Leadership.

Now, with the help of a post-expedition $11,999 grant from COL, she will spend a year studying the samples she brought back to investigate the effects of compaction on the magnetic inclination in ocean floor sediments.

Novak’s research is part of her master's thesis, “Investigating the effects of compaction on magnetic inclination in the Nankai Trough,” and may be used to further what we know about earthquake hazards in Japan and at home off Washington’s coast.

The application

In late September, mid-drive from her native Minnesota to Western, where she would be attending graduate school, Novak received a call from Geology professor Bernard Housen, her faculty adviser. He told her the IODP, an international partnership of scientists and research institutions organized to explore Earth's structure and history through scientific ocean drilling, was looking for scientists to go on an expedition to the Southeast coast of Japan.

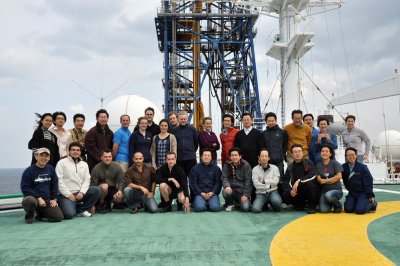

Novak said Housen helped her with filling out the majority of the paperwork. It helped that he had been on similar expeditions—in 1992 and 1996, going as far as Barbados and Costa Rica—and was already familiar with some of the scientists on board. Still, Novak’s qualifications speak for themselves: 22 years old at the time, Novak was hired on as a research assistant and was the youngest member of the Science Party, most of which were doctoral students and professors.

The training

The ship, Chikyu Hakken, which means “Earth Discovery” in Japanese, is a deep-sea drilling vessel capable of drilling for oil; the drill derrick, or crane, stands at 130 meters tall from the surface of the ocean.

To get to the Chikyu Hakken, already out at sea, the crew had to take a helicopter and because that was the only way to leave the ship in case of emergency, they also had to be able to safely ride and exit a helicopter—especially if it were to crash in the ocean.

“Basically, if the helicopter were to tip over upside down, we’d needed to know how to get out,” Novak says. For this they completed Helicopter Underwater Escape Training with four sets of emergency-preparation drills—practice escaping, underwater, from the passenger compartment of a helicopter.

“We went to a pool, we were put into metal cage, and then they flipped the cage upside down while [we were] strapped in,” she says. The participants had to unbuckle themselves and swim out; she did so successfully, thus qualifying for the expedition.

Life on board: Immersion in science

The four weeks were heavily spent on research. Each scientist worked one of the two 12-hour shifts seven days a week: noon to midnight and midnight to noon. Novak’s was the latter. They had almost daily meetings discussing sampling procedures and research, with each group presenting its results.

Although the researchers came from all over the world and spoke various languages, the common, uniting language was English. When not on their shifts, the scientists enjoyed what little downtime they had relaxing in common rooms, having get-togethers and doing what they love to do: talking science.

Housen said his expedition experience in the ‘90s was a similar immersion in science.

“You’re basically like an academic department on a ship for two months, all looking at the same problem,” he says.

Post-expedition research

Novak brought back as many as 550 samples of sediments. The researchers did not have proper equipment on the ship to examine the basalt samples they collected, so those samples were shipped to each scientist in May; everyone from the science party will have a year to work with their data—until about May 2012, when it becomes public.

On April 22, Novak defended her master’s thesis. She said the comments, questions and suggestions of the faculty and staff who attended the presentation helped better shape her research methods and approaches.

The scientists from the December expedition will reconvene again in December 2013 to compare their findings.

The big picture

The collective research could lend a hand to understanding Japan’s seismic activity.

The research Novak and the other scientists are conducting is a big part of the data used to look at plate tectonics and evolutions of fault zones. The findings could potentially lead to understanding Japan’s earthquake patterns and, because The Cascadia Subduction Zone plate is similar to Japan’s subduction zone, Housen says the research could bring us closer to better understanding our own seismic activity.

“It could improve quality of understanding of the whole Earth’s deformation,” Housen says.

He says Western faculty, specifically in the Environmental Science and Geology departments, often participate in similar expeditions and conduct similar research, although without proper acknowledgement or even community awareness, because the rigor of Western’s program is often understated.

“From the outside, Western doesn’t seem like an oceanography-rich school,” Housen says. “We don’t have an oceanography program that’s separate. But having a master’s student be selected to go on one of these cruises is a pretty big honor. It’s a testament to her ability but also to the reputation that Western has.”