Western’s Mike Etnier Using Clues From the Past to Look Into the Future of Alaska’s Pacific Cod Fishery

What can looking into the past tell us about the future? Western Washington University Anthropology Research Associate Mike Etnier and his colleague, Boston University Research Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Archaeology Catherine West, are hoping that digging deep into Alaska’s past can shed light on how to move forward to conserve and protect one of the region’s most important commercial fisheries: the Pacific cod.

Their results have recently been published in a Special Issue of the journal Quaternary Research published by Cambridge University Press, and can be found here.

Pacific cod has been one of the region’s most important subsistence fisheries for thousands of years, and as commercial species, with the commercial harvest usually generating more than $150 million each year. Etnier, West, and their collaborators want to help ensure that Pacific cod populations don’t fall prey to the same fate as their cousin species, the Atlantic cod.

The discovery in the 1400s of the “inexhaustible” Atlantic cod fishery on the Grand Banks off of Newfoundland changed the course of human history – the resource itself, along with the development of salted cod as a long-lived staple that could prolong time at sea, spurred the Age of Exploration into the New World.

For more than 500 years, fishers from New England and Atlantic Canada hauled in tens of millions of tons of cod until suddenly and disastrously in the late 20th century, after decades of overfishing, they were gone. The backbone of the workforce of Atlantic Canada was gutted, and more than 35,000 commercial fishers and fish-processing workers were no longer able to go to sea or to their canneries to earn a living. The fishery was shut down, and by 1993, the great Atlantic cod fishery was at about 1% of historic levels; the newest data suggests that the Grand Banks, even in total moratorium since the 1990s, won’t be a sustainable fishery again until at least 2030, almost 40 years after it was first shuttered.

This gaping hole in the cultural, historic and economic consciousness of New England and Atlantic Canada spurs the research of Etnier and West.

“What happened on the Grand Banks is one of humanity’s great case studies in overfishing,” said Etnier.

The great leap forward in postwar technology allowed for more efficient harvesting of cod, in bigger boats over longer periods of time. Combined with rapid ecological changes and a political unwillingness to make large-scale adjustments to the fishery, the Grand Banks, once thought to be limitless in its fishing potential, was now largely empty of cod.

Bones from the past

Along with colleagues and collaborators from NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Etnier and West surmised that the enormously important and lucrative Pacific cod fishery of the Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska could share the same fate as that of the Grand Banks unless more care was taken and more research done before it reached a crisis level.

West said an important part of that puzzle – and one in which archaeologists could play a meaningful role -- lay in not only knowing the health of the fishery now, but the health of the fishery years ago. Records exist for fish sizes and catches of the commercial catch going back about 80 to 100 years – not nearly enough data for a truly long-term perspective.

“What if we could provide data from 6,000 years ago instead of just 100?” she said. “We have a huge dataset to draw from – using the archeological records of the Indigenous peoples from coastal villages to find out as much as we could about what they were catching, and where.”

Beyond simply looking at how many cod are in a given area, a chief measuring stick of the health of a fish population is the size of the biggest fish being caught: the biggest, oldest fish provide an incredibly important snapshot into population health. As the Grand Banks fishery dwindled, the biggest fish being caught there continued to shrink until few if any full-grown fish were even being caught, a sure sign of a population in collapse; fewer and fewer fish living long enough to lay eggs is another marker of a population in freefall.

By examining Pacific cod bones from museum collections and from waste sites left by the Indigenous peoples of the North Pacific coast centuries ago in places like the Kuril Islands, Kodiak Island, the Alaska Peninsula and the Aleutian island of Unalaska, Etnier and West have been able to ascertain a key fact: the biggest Pacific cod pulled from the ocean by the Indigenous peoples of the region thousands of years ago are about the same size as the biggest fish hauled in today.

“This is remarkable for a number of reasons,” said Etnier. “First, that thousands of years ago, the peoples of the Aleutians could paddle 15 miles out to sea in one of the stormiest places in the world, drop down 300 feet of kelp fishing line with a bone hook, and haul in cod that are just as big as the biggest cod caught today.”

“Just as importantly, we can look at these size comparisons and use those numbers to see that by and large, the fishery was managed well thousands of years ago, and in terms of fishing pressure, is being pretty well managed now,” he said. “But it’s not just fishing pressure that we have to worry about.”

Every bone tells a story.

Bridget Lindquist, a biological anthropology major from Woodinville, saw an incredible research opportunity in Etnier’s lab in digging through and examining the thousands of cod bones pulled from the middens.

“Even when we spent hours sorting hundreds of tiny bones and fragments, we would always find something cool to look at under the microscope. I never know what unusual bone or pathology we might look at. Did you know that ducks have bones in their tongues? I didn’t, until we found one in a midden sample,” she said. “Every bone tells a story.”

The cod research hasn’t just been an academic interest for Lindquist during the stressful period of the pandemic, either; it has been a type of therapy that has reduced her stress load and allowed her to focus on her next steps.

“I’ve made good friends and met some really valuable professional contacts through the lab. I think what I value most though, is the confidence this work has helped me find in myself. Getting ready to graduate from college is more than a little bit terrifying, but when I’m in the lab I don’t feel scared at all,” she said.

With Lindquist’s help, Etnier and West were able to amass enough data to draw that important positive conclusion about the size of the biggest cod in the fishery today vs. as long as 6,000 years ago.

But when The Blob arrived, it was clear to the researchers that a completely different factor – a warming ocean -- is at least as big a threat to Pacific cod as fishing.

Meet ‘The Blob’

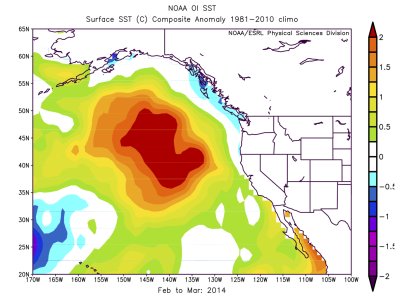

Like El Niño and La Niña, The Blob is an oceanographic occurrence that can be measured and observed, but what triggers its arrival and departure is less well known.

As its name suggests, The Blob is a huge patch of water in the North Pacific that is much warmer than it should be – and it brings with it not just a dramatic rise in sea temperature over a patch of ocean a thousand miles wide and 300 feet deep, this water is also much less nutrient rich, essentially turning a lush marine oasis into a desert.

“The Blob just wipes out cod, feeder fish, sea birds, everything it touches,” West said. “Regulating the fishery is important. But understanding what is causing The Blob is going to be crucial to the ecological and economic health of many of the Alaskan fisheries.”

Etnier agreed.

“If the warming ocean is killing the prey species cod need to eat to survive, or dropping the survivability of cod eggs, all the effort in the world to manage the fishery from a commercial perspective won’t matter,” he said. “We’ve been able to show from a historical perspective how healthy the fishery has been, but The Blob is a wild card.”

In the end, the viability of this resource may come down to efforts that need to happen across the planet, and not just in the Gulf of Alaska or the Bering Sea.

For more information about his Pacific cod research, contact Mike Etnier at mike.etnier@wwu.edu.