Tuesday Q&A: The Electoral College - Working as intended or a democratic dinosaur?

In this edition of Tuesday Q&A, Western Today chatted with WWU historian Hunter Price and political scientist Todd Donovan about one of the most divisive features of our Democracy: the Electoral College. Only five presidents have been elected even after losing the popular vote, but two of those are since 2000: George W. Bush and Donald Trump.

Is the Electoral College an archaic remnant of our post-Revolution past or a vital cog in our election process? Read on, and decide for yourself.

Hunter Price

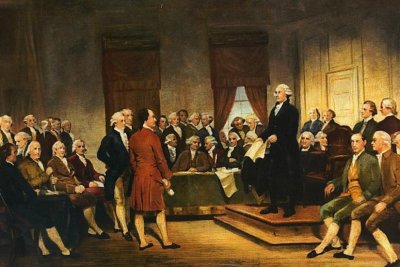

WT: Why did the framers of the Constitution decide to use the Electoral College system?

This answer depends on who we mean by “framers.” One perspective comes from Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 68. In 1788, he declared the electoral college to be among the most popular measures in the proposed Constitution. It was an improvement over the original plan (put forth in the Virginia Plan) of allowing the Congress to elect the president and vice-president. Election by Congress, some feared, would undermine the desired separation of powers.

Congress, in effect, would become what Madison and many others feared most, a faction, a group of citizens allied in pursuit of special interest and willing to subvert the public good to achieve it. This particular faction would hold the president and vice-president in its debt, and come to collect, especially at re-election. Better would be to have a “spontaneous” gathering of electors who would vote and then disband forever. Hamilton described a second virtue of the electoral college. It solved two problems of direct popular election of executive officers. The process would be insulated from the “tumult and disorder” he believed would result from direct participation by the people. It would also ensure that a man of the first moral rank and wisdom would emerge from the individual states.

But Hamilton was arguing a position, not analyzing objectively. Many opposed his view, including some members of the Constitutional Convention and others who opposed the ratification of the Constitution. The electoral college was in fact the product of the internal politics of the Constitutional Convention, and early on, many other delegates preferred that Congress elect the president. Support tipped in its favor during committee meetings within the Convention.

The slaveholding South in particular stood to benefit from the electoral college. The “three-fifths compromise,” which allowed the slaveholding states to count enslaved persons in their population for receiving seats in the House of Representatives (without having to extend those persons freedom, voting rights, or other basic claims of citizenship), also determined the number of electors each state received. As a result, the South was protected from the growing population of eligible voters in the North whom they feared would turn the federal government against the Southern states.

WT: Was an electoral college system in place elsewhere at the time?

The U.S. electoral college was not an original idea. At various times, groups of electors, often members of a nobility, elected a political leader. Probably the two most well-known examples existing at the time of the Constitutional Convention were in the Holy Roman Empire and the Catholic Church. German political and ecclesiastical leaders had long gathered to elect the Holy Roman Emperor, who then ruled over portions of Western and Central Europe. For much of that history, the Pope, as the head of the Roman Catholic Church, crowned as Holy Roman Emperor, but the Pope himself was chosen through a process resembling an electoral college. After a Pope died, the College of Cardinals convened, deliberated, and named a new Pope.

WT: How are electors chosen, and as our society has evolved, has this process remained fair?

Today, presidential candidates generally receive all of the electoral votes from each state where they won the popular vote. Originally, popular voting and electoral college voting were not clearly linked. The Constitution instructed state legislatures to choose, according to their own choice of qualifications, “a number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives” serving the state in Congress. In the 19th century, some states did not administer popular voting for the presidency.

Despite Hamilton’s claim that the electoral college was popular and uncontroversial, it has been involved in political intrigue since its early years. Its function was tweaked by the 12th Amendment, which remedied the situation in which a candidate for the vice presidency could claim the presidency, as Aaron Burr attempted on Thomas Jefferson shortly before, as we all now know well, shooting Alexander Hamilton in a duel. More important reforms came in the 1820s and 1830s when many states changed their laws and allowed popular voters, rather than legislators, to choose electors. This was part of the wave of democratization that significantly expanded voting rights, mostly for white men, in the first half of the 19th century.

Has the process remained fair? One might ask whether the process was ever fair.

From its beginning until the 13th and 14th Amendments, the selection of electors was tied to the nation’s embrace of chattel slavery. Today, some supporters argue that the electoral college helps to protect against a handful of metropolitan areas dominating elections. Some critics decry an institution that can help to deliver the presidency to a candidate who did not win the popular vote. Whether the electoral college and the rules that guide it are fair is a question for Americans and their representatives to debate and decide.

Since 2000, two presidents have been elected without winning the popular vote, and some Americans have wondered if the electoral college is an archaic check on democratic forces. Whether such questions about our election practices will develop sustained momentum is yet to be seen.

Todd Donovan

WT: Do you think the electoral college, in terms of elections in this country in say the last 100 years, has worked as the framers intended?

I don't think we can talk about framers' intent here, as they had no idea what they were doing. They didn't give this much time or thought. They had no conception of elections with mass participation, nor any sense of political parties or elections on a national scale. The electoral college was not designed to work in conjunction with popular voting.

Originally, the process took months. New York could not figure out how to vote, so it didn't. The system failed spectacularly in 1796 in our first contested presidential election when it elected a president and vice president from rival parties. That's like having Hillary Clinton being Donald Trump's VP.

It crashed spectacularly in 1800 when it resulted in a tie between two candidates from the same party. That forced a Congress dominated by the rival party to select the president. The 12th Amendment didn't fix that problem. We came close in 1948, 1968, and closer than folks realize in 2016, to a result that would again force Congress to pick a president.

People might be semi-ok with the Court doing that in 2000, but not Congress. It will be a crisis.

WT: What other modern democracies use an electoral college system, and what others do not? Are there good examples of democracies working both with and without a system like this?

The Catholic Church uses something similar to select popes. Obviously, that is neither modern nor a democracy. Kazakhstan has one. So, no, not really.

WT: When the electoral college runs against the popular vote, as it did in 2016, do you think that is a sign that it is working as intended or dysfunctional?

Again, there was no intent that applies to popular voting. This system came from a constitution designed to protect slavery in an era where hardly anyone voted in presidential elections.

It was dysfunctional from the start, and remains so. Some now make the argument that the electoral college is a core aspect of federalism - a sort of cleaned up 'states rights' argument. So, if you argue it was intended to thwart popular control over electing a president, then maybe it's not so dysfunctional.

Hunter Price has taught at Western since 2014. He received his doctorate from Ohio State University in 2014 and his major areas of research include politics, society, and religion from the American Revolution through the Civil War Era.

Todd Donovan has been at WWU since 1991. He received his doctorate from the University of California at Riverside and his research focuses on elections and representation. He served as one of Washington State's presidential electors (alternate) in 2004.